Golden Memories: USA Kicks Off Olympic Women's Soccer in 1996

Twenty-Five Years Ago the USWNT Captured Its First Gold Medal

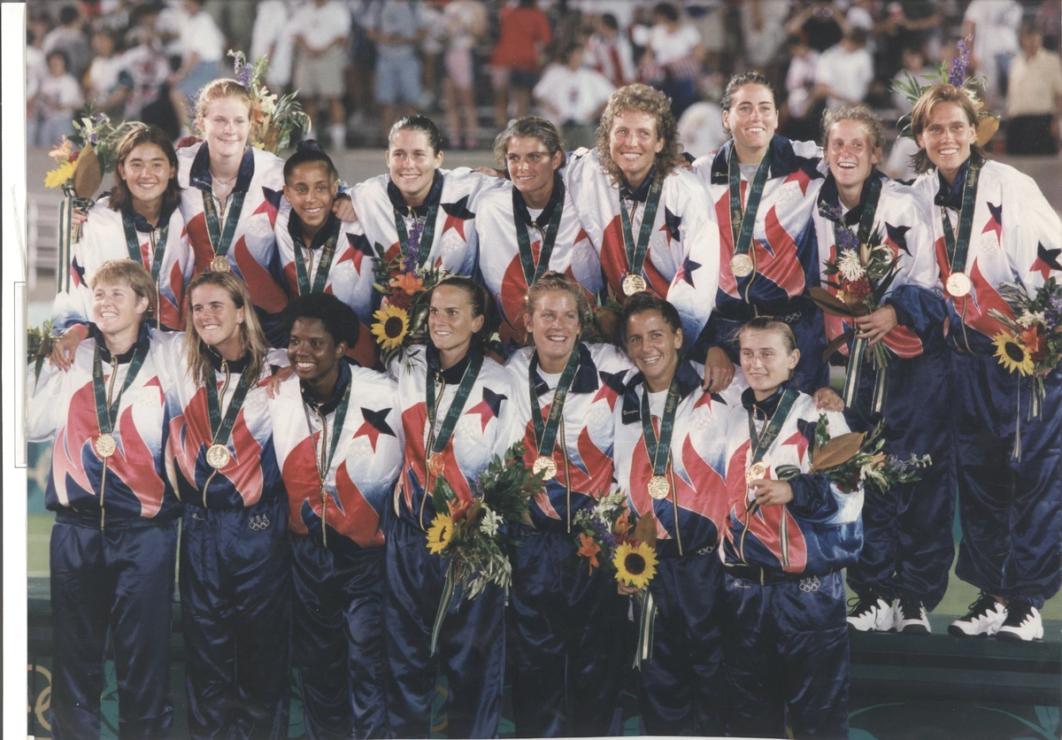

Sixteen women stood on the winner's podium, proudly wearing their well-earned gold medals, awarded in front of a crowd of 76,489 spectators at Sanford Stadium on the University of Georgia campus on Aug. 1, 1996. The crowd – at the time the largest to watch a women's soccer game anywhere in the world – cheered and sang along as the anthem played during the medal ceremony, honoring a team that secured the first Olympic women's soccer gold medal.

It was a grandiose moment for all the players, including Shannon MacMillan, who -- after originally being denied a spot at pre-Olympic residency training camp -- fought her way onto the team, and then scored the semifinal extra time winner against Norway and the opening goal in the final against China PR.

"My journey to that point had been so hard," she said. "I had to overcome such adversity that getting that gold medal was one of the most intense and amazing feelings ever. To be holding hands with my teammates who had become sisters and family through the residency camp process was a moment that can't be compared."

Other women standing on that podium agree.

"You received the medal that you've dreamed about your whole life, that you've seen on so many other athletes receiving," said Tiffeny Milbrett, who scored the winning goal in the 2-1 gold-medal triumph. "It's all such a shock to the system, but in such a positive way, because it was nothing like you had ever gone through in your life before. It's transformative."

At the time, major international women’s soccer championships were relatively new. The first Women’s World Cup was held in 1991 and the International Olympic Committee added the women’s soccer two years later, making the 1996 Games in Atlanta the first women’s soccer.

The Olympics were a big deal for the American players, who had dreams of being Olympians when they were growing up, even when women’s soccer wasn’t an Olympic sport.

"Participating and winning the world championship in 1991 was incredible, but as a player, I have always craved the opportunity to play in the Olympics," USA forward Michelle Akers said in 1993. "It is great for women's soccer around the world, particularly in the United States, where the Olympic Games are put on such a high pedestal. This gives women's soccer the opportunity to be the center of attention more than any other event."

It also gave her teammates an opportunity of a lifetime.

"It was pretty amazing! I grew up enamored with the Olympics and would always be glued to the TV when they were on, both summer and winter," MacMillan said. "To finally have the sport that we all loved and were so passionate about be accepted was a dream come true. Even more so to be a part of that amazing group of 16 on the final roster."

The same went for goalkeeper Briana Scurry.

"It was a dream come true because I wanted to be an Olympian since I was eight-year-old," she said. "I saw the Lake Placid ice hockey team do the impossible, by beating the USSR. I declared to my parents that I want to be an Olympian.”

Milbrett had her ambitions, too. In 1989, her high school varsity soccer coach asked players their goals. Milbrett’s was the Olympics.

"She's like, 'Well I don't know if I have the heart to tell you, but I have to tell you. Women's soccer isn't in the Olympics.’ I was like, 'That's okay, I'll just play for the boys.’ I was so naïve," she said.

That inaugural Olympic Tournament had just eight teams competing in two groups. The top two finishers in each group advanced to the semifinals - the medal round. Team rosters included only 16 players. To make matters more challenging, squads got just one day of respite between group-stage matches, meaning they played three games in five days, hardly a schedule that befitted world-class players. The medal round participants got a couple of extra days of rest.

The USA began on July 21, 1996, with a 3-0 win over Denmark in 102-degree heat in front of 25,303 fans at the Citrus Bowl in Orlando, Fla. Mia Hamm scored one goal and set up another. Tisha Venturini scored the first goal in women's Olympic history in the 37th minute.

"Our focus was totally on that first game," Scurry said. "You’ve got to get those first points at all costs. That sets you up for the entirety of the tournament. You also make a statement in your group, in the tournament. There's a lot of psychological advantages. If you don't get the three points, think of the alternative. You lose that first game or tie; you are chasing the rest of the tournament."

With nine minutes remaining in the USWNT's 2-1 win over Sweden in Orlando before 28,000 fans on July 23 in the second group stage match, head coach Tony DiCicco experienced his worst nightmare as Hamm was taken out off the field on a stretcher with an ankle injury after colliding with goalkeeper Annelie Nilsson. "We all held our breath," he said then.

DiCicco, who passed away in 2017, held Hamm out of the last group match. That was a scoreless draw on July 25 with China PR in front of 55,650 at the Orange Bowl in Miami, Fla., setting up a semifinal confrontation with Norway in Athens.

"There's no way we were going to lose that game," said Scurry. "I felt like we were going to prevail."

The Americans would, but not before Norway’s Linda Medalen, who loved playing the villain against the USA, put the Norwegians ahead, striking from 12 yards in the 18th minute. It appeared the game might have a similar result as in 1995 when Norway beat the USA 1-0 in the 1995 World Cup semifinal, until defender Hege Riise was called for a handball in the penalty area.

Akers, battling Epstein-Barr Syndrome -- an energy sapping ailment, converted the ensuing penalty, sending her shot to the lower left as goalkeeper Bente Nordby dove in the opposition direction.

"Nothing surprises me about Michelle," DiCicco said at the time. "A lot of people have counted her out."

The match went to “Golden Goal” overtime (which was used at the time) and six minutes into extra time, MacMillan replaced Milbrett. Four minutes later, Julie Foudy raced down the right flank and set up MacMillan, who scored from 12 yards and a 2-1 victory.

MacMillan admitted her emotions were "Very hard to put it into words."

"To be out on the field playing and scoring important goals was beyond anything I could have imagined," she said, adding that the goal “was surreal. It felt like everything was in slow motion."

MacMillan’s magic continued in the 19th minute in the gold medal match at the same venue four days later. Despite playing with an injured ankle, Hamm set up both scores. Kristine Lilly sent a left-wing cross into Hamm, who drilled a shot off the left post. The rebound ricocheted to MacMillan, who slotted a four-yards home for her team-high third goal of the tournament.

Like MacMillan, Milbrett also had worked her way onto the team, thanks to DiCicco. "The biggest thing for me is that he's the first coach that really give me my chance to shine," she said. "I felt like he was a decent man. He had his heart in the right place."

With the score deadlocked at 1-1 in the 68th minute, Milbrett found herself at the right place at the right time.

Defender Joy Fawcett intercepted a pass on the right side and dribbled to midfield before passing to Hamm. Fawcett never stopped running toward the penalty area as Hamm sprung her with a perfect through ball.

Milbrett saw the play developing and took off on a long run into the penalty area, ready for a cross, a poor clearance or a rebound. She couldn't believe no one had picked her up.

"It's almost as if they forgot about me," she said. "I have no idea I was left so alone."

Fawcett sent a cross the box toward Milbrett.

"No goal is easy to score, but when you're left alone and your teammate leaves you a cross so absolutely perfect, it's one of the easier moments that you can have,” she said. “It just comes down to your technique, placement and timing of getting that shot off and placing it. Just avoid the goalkeeper."

Which she did from six yards; 2-1 USA.

Milbrett celebrated with a somersault. The USA's focus switched to closing out the game.

Twenty-two minutes and some stoppage minutes time later, the stadium erupted again. The Olympic champions saluted the fans, dancing around Stanford Stadium with American flags before the medal ceremonies.

After the celebrating and signing subsided, Scurry had some unfinished business.

Before the Olympics, Scurry was asked by a Sports Illustrated reporter what would she do if the USA captured the gold medal. To which she replied, "I will run naked through the streets of Athens.”

"It got to be like a huge thing," said Scurry, who continually was asked when she was going to run.

"I'm going to run when we win and not before," she said. "Don't remind me about it. I've got to win the thing first."

In what has become part of U.S. Soccer lore, around 2 a.m., Scurry had a friend drive her to a side street in Athens. She took off her clothes in the car, put a towel on, left the car, threw the towel down and ran down the street and back while wearing her medal. Her friend taped it "for verification purposes only," Scurry said at the time.

Scurry looked back at that with a laugh, although duplicating such a run today would have its obvious challenges.

"Nowadays, maybe not,” she said. “Everybody and their brother has a phone and a camera."

Today, it's relatively easy to watch most soccer games on a phone.

In 1996, however, the USWNT's history-making triumph was a well-kept secret on the airwaves. NBC, which broadcast the Summer Games, had all but ignored both soccer tournaments until the women’s final. It gave viewers periodic updates and interviewed U.S. players after the medal ceremony, but did not show the game live.

The lack of coverage wasn’t going to stop the momentum. The USA women's basketball, softball and gymnastic teams also brought home the gold, harkening a rise of female sports.

"There are worldwide implications," DiCicco said in 1996. "Seventy-six thousand fans shows there's incredible interest in the women's game. This is something that should be taken very seriously. The women's sport is ready to explode."

Twenty-five years later, the sport has and continues to climb to new heights and that medal podium in Athens was a key launching point for its success.